Louise Eldridge – Policy and Communications Officer at CORE

Credit: Brian Minkoff / Shutterstock.com

The 2019 general election ended months of political uncertainty and laid a path for a new legislative agenda. In their election manifesto, the Conservative Party stated its commitment to “strengthening the UK’s corporate governance regime.” We explore what’s happened to date and take a look at some recent proposals for corporate governance reform.

A new regulator with teeth?

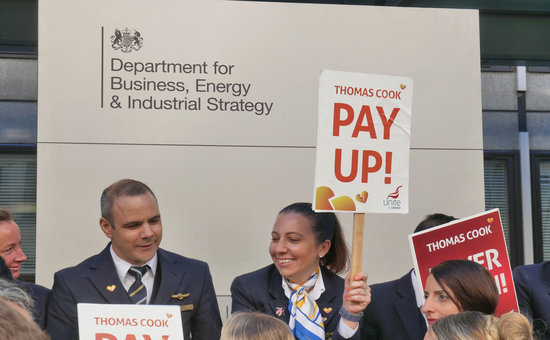

The Tory manifesto included a pledge to “reform insolvency rules and the audit regime so that customers and suppliers – and UK taxpayers – are better protected when firms like Thomas Cook go into administration.”

Regulator the Financial Reporting Council (FRC) had already been facing intense parliamentary scrutiny over its lacklustre response to corporate scandals such as the Carillion collapse. It is expected that the Government will seek to implement a number of the recommendations arising from the Kingman Review (including that the FRC is replaced with an independent statutory regulator called the Audit, Reporting and Governance Authority, or “ARGA”) and the Brydon Review, which examined the quality and effectiveness of audits.

A series of citizens’ juries, organised for the Financial Reporting Council by BritainThinks revealed support for a much tougher regulator to hold individuals as well as companies to account. Citizens called for companies to act in the public interest and felt that a regulator should be able to sanction individual board members as well as accountants, audit partners and their firms.

Executive pay and company boards

The manifesto also committed to “improve incentives to attack the problem of excessive executive pay and rewards for failure”, but provided no further details.

Reforms introduced in the wake of the 2016 Corporate Governance Green paper created new reporting requirements on executive pay, but Theresa May’s pledge to put workers on company boards was, unfortunately, swiftly dropped.

One other option for reform is to ensure all workers share in the profits of a company. Cross-party think-tank the Social Market Foundation has proposed a new provision in company law requiring Directors to ensure workers’ pay rises over the long-term, and a kitemark to enable investors to judge firms on how they pay and train their staff.

From profit to “purpose”

The belief that the sole purpose of business is to maximise profits for shareholders is fast losing favour. In 2019, research by Oxfam and a new report by the TUC & High Pay Centre revealed the alarming increase in shareholder profits at the expense of workers, society and the environment. From 2014 to 2018, nominal returns to shareholders across the FTSE 100 rose by 56%, growing nearly seven times faster than the median wage for UK workers, which increased by just 8.8%.

The calls to move away from a singular focus on shareholders’ interests come from some surprising arenas, including the Business Roundtable (a US association of leading chief executives) and the UK’s Financial Times, which is urging a “rethink” of capitalism.

New research conducted by the British Academy’s Future of the Corporation project found that the UK has a particularly “extreme” form of capitalism and ownership, and proposes eight principles to guide policymakers and business leaders to bring about “purposeful” business, including that “corporate law should place purpose at the heart of the corporation.”

Calls for reform of the Companies Act 2006

The British Academy is not alone in calling for a reform of company law, which as it currently stands, enshrines the shareholder primacy model.

The Companies Act 2006 contains a rather ambiguous requirement for the Directors of UK companies to “have regard to” social, environmental and community issues in their running of the company. Campaigners have long called for changes to the Act to put social, environment and employee interests on an equal footing with shareholder profit.

Recently, law firm Bates Wells weighed in with a draft Company Purpose (Amendment) Bill, which would displace shareholder primacy as the orthodoxy in British board rooms. The Bill is backed by a growing group of influential companies, business leaders and academics.

Corporate governance must be coupled with corporate accountability

To date there are no examples of a company or directors being held to account for failure to “have regard” for their wider stakeholders. To end corporate practises that harm people and the environment, we also need to ensure that firms and corporate leaders can be held accountable for serious misconduct.

To this end, as well as a desperately needed reform of corporate structures and business models, CORE is calling for companies and directors to be required to take action to prevent human rights abuses and environmental damage (in their own operations and supply chains, regardless of where the harm took place) – and to be held liable if they fail.

A new report from the British Institute of International and Comparative Law (BIICL) finds that a “failure to prevent” mechanism for corporate human rights harms, modelled on the UK Bribery Act, would be feasible.

The vast majority of companies surveyed by BIICL expressed frustration at the current lack of clarity regarding firms’ human rights responsibilities. Tellingly, however, while businesses demonstrated an appetite for smart, clear regulation, BIICL found the legal elements relating to liability were in general not supported by business.

Yet as experience of the Companies Act demonstrates, rules without accountability do not change corporate practices. Momentum is growing across Europe for laws to hold companies for harming people and planet. If the UK wants to avoid becoming a safe haven for irresponsible firms, it will have to keep pace with this trend.