For the last few days, the members of the most exclusive club in the world, the G7, have been meeting by the seaside. Supposedly, top of the agenda was fighting inequality.

Two years ago they met to promote inclusive growth. Since then 82% of new wealth has gone to the richest 1% while the world’s poorest 50% got no better off. It’s as if, behind closed doors, they were talking about promoting exclusive growth.

Research published by Oxfam last week concludes that the policies G7 members are pursuing are making inequality a whole lot worse. Tax cuts for the rich, crooked politics, failure to tackle the climate crisis and a sexist economy are among the G7’s ‘deadly sins’.

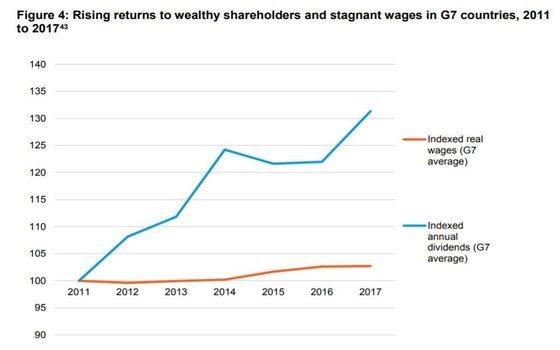

But what really caught people’s attention is this graph, showing that between 2011 and 2017 average wages in G7 countries grew by less than 3 percent, while dividends to wealthy shareholders grew by 31 percent.

A vivid demonstration of the G7’s neo-liberal model of capitalism designed to put shareholders first. A model whose defining feature is excessive returns to capital at the expense of labour. A model that’s been exported around the world, responsible for deepening the extreme inequality crisis and dividing societies.

Profit to shareholders comes at a cost – and not just to wages of those working in G7 countries. Oxfam’s inequality and supply chain campaigns are filled with horror stories of the human suffering that comes from a shareholder first economy – like shrimp workers in Asia who are forced to do pregnancy tests and then get fired when they become pregnant, or poultry workers in the US who are forced to wear nappies because they don’t get toilet breaks.

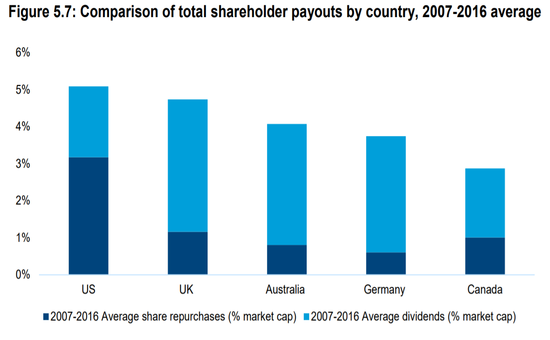

Combine consumer demand for cheap products with shareholder demand for profit and the people with the least voice and power are the ones who suffer. The UK is second only the US in shareholder enrichment.

Oxfam’s been campaigning to get the laws in the UK that entrench this system changed. When the government published their Green Paper on Corporate Governance last year it opened the doors to putting employees on boards, limiting executive pay and reforms to the part of the Companies Act that requires directors to put shareholders first (Section 172). We thought we had an opportunity.

With the CORE coalition of NGOs and Trade Unions we submitted evidence, met with civil servants and held roundtables with policy makers. Many businesses, investors and (privately) policy makers were supportive of our proposals for radical reform towards a stakeholder led economy. But at the end of the day, the corporate business lobby won over and the only tangible change has been new reporting requirements for executive pay.

The mood music is changing though. According to Oxfam polling, 59% of the public think businesses have a responsibility to reduce poverty and inequality and 64% support capping CEO pay to no more than 20x average worker pay.

The business lobby is trying to head off criticism. In the US this week 181 CEOs claimed to disavow shareholder primacy and instead promote a ‘statement of purpose.’ For many, these mealy words with no solid commitments were quickly seen through and disregarded as purpose washing.

With a UK general election potentially around the corner, all political parties should be seriously considering policies to tame shareholder greed. With that in mind, Oxfam is calling on our political leaders to:

- Tackle excessive profits going to shareholders. Companies need to make a profit, but to what extent and at whose expense? In Ecuador, companies were banned from issuing a dividend until they were paying living wage. We think countries around the world should adopt a similar approach.

- Rebalance power between workers and shareholders. Evidence for workers on company boards is compelling. Countries with strong worker participation have higher employment rates, their poverty and inequality rates are lower and they use fewer fossil fuels.

- Increase employee ownership. Where employees have become owners in a firm, productivity and efficiency has increased and the company has become more resilient during economic downturns. Employees also have higher wages, better employee benefits and more job security.

- Reduce disproportionately high wages for CEOs. They earn in days what their workers earn in their entire lifetime. Making CEOs commit to a maximum pay ratio, ideally no more than 20 times that of their employees, and banning perverse – profit fixated – incentives, would go a long way to reduce inequality.

- Reform the responsibilities of directors. Company Law in many countries requires directors to act first and foremost in the interest of shareholders. It’s what enshrines shareholder primacy into law. Oxfam believes the duty of directors should be to balance the different stakeholder needs, based on a principle of putting those with the greatest needs, poor and otherwise marginalised communities, first.

All of that said, the future of business lies in equitable models that serve their workers, their suppliers and their communities by design. These include social enterprises, innovative new cooperatives and a range of hybrid models. Businesses that pursue a social mission and give much greater power and profit to workers, farmers and communities. Businesses that can’t be corrupted by billionaire shareholders whose only interest is profit.

We must call an end to the dominant model of business and finance that puts shareholders first – through regulations and incentives that level the playing field and move equitable business models from the periphery to the mainstream.

Political leaders who fail to do so may find that when the music stops there’s no chair left to sit on.